Jonathan L. Finlay, MB ChB, FRCP (Lond.), FRCPCH, Director, Neuro-oncology Program; Elizabeth and Richard Germain Endowed Professor of Pediatric Cancer, Division of Peduiatric Hematology, Oncology and Blood & Marrow Transplant, Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Professor of Pediatrics and Radiation Oncology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

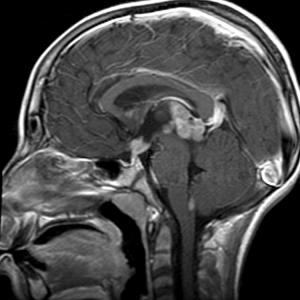

(image provided by Gilbert Vezina, M.D., Children’s National Medical Center, DC)

The family of tumors known as germ cell tumors can develop anywhere in the body, most commonly in the male testicles and female ovaries, but also in other locations in the pelvis, abdomen, chest and brain. These tumors are considered to arise from nests of embryonic cells that were traveling along the primitive notochord during early fetal development down to their usual locations (ie. to the genitals), but somehow became arrested in their migration. Those tumors arising in the brain do so mainly from mid-line locations of the pineal gland (at the rear end of the third ventricle) and the suprasellar and hypothalamic region (at the front end of the third ventricle)

What causes these primitive embryonic cells to undergo transformation into cancers is not known. These tumors are found only very rarely in more than one family member, so a genetic association is not the usual reason. Two genetic conditions, Down syndrome and Kleinfelter syndrome, are known to be associated with an increased incidence of germ cell tumors of the brain (in Down syndrome children) and of all types of germ cell tumors (in Kleinfelter syndrome. Of interest, however, is that germ cell tumors arising in the brain (but not other types of germ cell tumors) are far more common in South-East Asian countries than in North or South America or in Europe. No environmental factors have been linked to the development of these tumors, except that the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES) used several decades ago to stabilize unstable pregnancies and known to be associated with the development of vaginal cancer in offspring of woman taking the drug during pregnancy, has also been less convincingly linked to testicular cancer in offspring. Testicular cancer (but not other forms of germ cell cancers) has been clearly associated with the failure of testicles to descend from the abdomen into the scrotal sac of young boys.

The average age at which germ cell tumors of the brain present is around the onset of puberty. However, some will present in infancy and early childhood, and others present in adult life. The age at onset is important in that younger, pre-pubertal children will experience more profound damaging effects of radiation therapy – and such younger children are usually the very ones that harbor the most malignant types of CNS germ cell tumors that require more aggressive treatments in order to cure them. One exception is the development of intracranial germ cell tumors in infancy; such tumors tend to be low-grade mature teratomas which can be best managed by surgical resection only, if safely achievable.

The malignant germ cell tumors of the brain represent less than 5% of childhood brain tumors, and yet are also one of the most curable of brain tumors, being exquisitely sensitive to both radiation therapy and chemotherapy. However, their very rarity, and the complex heterogeneous forms they take, has led to a poor understanding of these tumors and how best to diagnose them and treat them. In recent years, the use of both combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy has become the standard of care for children and adolescents in North America, Europe and Japan. However, debates ensue as to when surgery should be used for these tumors, what doses and fields of irradiation should be used and when can milder forms of chemotherapy suffice as opposed to more intensive chemotherapies.

The Different Types (Pathology) of Germ Cell Tumors of the Brain

One significant difficulty in understanding germ cell tumors arising in the brain is that they often contain more than one type of germ cell tumor. The most widely accepted classification of such tumors is as follows:

| Germinoma | approximately two thirds of all brain germ cell tumors | |

| Germinoma with Mature and/or Immature and/or Teratoma | approximately 10% of all brain germ cell tumors | |

| Mixed Malignant Germ Cell Tumors *containing one or more of the types: Yolk Sac Tumor (YST) – also known as Endodermal Sinus Tumor (EST) Choriocarcinoma (CC) Embryonal carcinoma (EC) Germinoma (G) Mature Teratoma (MT) Immature Teratoma (IT) | approximately 25% of all brain germ cell tumors |

Therefore, in over one third of cases, the patient will have tumors composed of more than one type of germ cell tumor. It is critical for treating physicians to be aware of this, because each of these components is best treated in differing ways!

Diagnosis of Germ Cell Tumors of the Brain

Patients with pineal region tumors usually present with the acute effects of these tumors compressing and obstructing the nearby ventricular system, causing hydrocephalus (excess fluid in the chambers of the brain), raised pressure within the entire brain and consequently headaches and vomiting. Characteristically, certain eye changes are also noted due to downward compression of the tumor on the midbrain (Parinaud’s Syndrome). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan will reveal a tumor in the pineal region – but that in itself does not confirm the diagnosis of a germ cell tumor. Other tumors can look virtually identical on MRI, such as pineoblastoma, ependymoma and malignant gliomas.

Patients with suprasellar/hypothalamic region tumorspresent usually with a much longer history, sometimes over many months or even years, of vague symptoms including increased thirst and urination, increased fatigue, poor growth and declining school performance. These signs are largely due to destruction of the hormone-producing cells located in the hypothalamus and its connection down to the pituitary gland (the pituitary stalk or infundibulum). Again, an MRI scan will demonstrate a tumor in this location, but this does not confirm the diagnosis of a germ cell tumor; gliomas of the optic pathway are not infrequently confused with germ cell tumors in this location, as can other types of tumors.

One of the unique characteristics of germ cell tumors arising in the brain is their production and release of chemicals into the blood and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) called tumor markers. The presence of these tumor markers in either location can often confirm that a tumor seen in the pineal or suprasellar regions on MRI is indeed a germ cell tumor. However, nothing is ever quite that easy! There are two germ cell tumors markers in common use today, but not all germ cell tumors produce them, and some do so only in small amounts. The presence of such markers and the levels at which they are present in the blood or CSF are not absolutely diagnostic of specific germ cell tumor types. These tumor markers can thus be misleading in identifying germ cell tumors and specific germ cell tumor types, so that the results of germ cell tumor marker tests must be interpreted with caution. The germ cell tumor markers and their associated tumor types are shown below:

| Alpha-fetoprotien (AFP) | Considered diagnostic of Yolk Sac Tumor (but also seen at low level in some cases of Immature Teratoma and Embryonal Carcinoma. |

| Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Beta (HCG- β) | Considered diagnostics of Choriocarcinoma, but now recognized to be produced at “low” levels in pure Germinoma, as well as some cases of Immature Teratoma and Embryonal Carcinoma. |

A significant problem that now exists is that some children with pure germinomas continue to be over-treated as more malignant tumors. This is because an HCG-β level in excess of 100mg/dl is currently, on North American and European (but not Japanese) trials, considered diagnostic of a more malignant choriocarcinoma tumor. There is no basis in fact for such an arbitrary cut off. On the contrary, it is clear that children with pure germinomas can have much higher levels of HCG-β in their blood or CSF. Biopsy-proven children with germinomas and with HCG-β up to almost 200mg/dl have been successfully cured with the less intensive germinoma treatments.

The Role of Surgery in the Treatment of Germ Cell Tumors of the Brain

Unfortunately, the germ cell tumors of the brain arise in deep-seated locations that, even with modern day neurosurgical and imaging techniques, can lead to significant damage if operated upon by inexperienced hands. The rarity of these tumors means that only those neurosurgeons – and largely pediatric neurosurgeons – who work in major medical centers, have sufficient experience and expertise to tackle these tumors.

In general, a biopsy (a small sample of tumor tissue) is essential if the MRI scan shows a tumor in the pineal or suprasellar regions, and the tumor markers in both serum and CSF are not elevated or only minimally elevated. Patients with pineal region tumors usually present with hydrocephalus that needs to be corrected by the placement of a shunt; accordingly, many skilled neurosurgeons today will combine the placement of a third ventriculostomy (a totally internalized shunt) with a tiny biopsy of the tumor, performed through a much less invasive endoscopic procedure. However, the tumor tissue sample is often extremely small by this approach, and may not be representative of the entire tumor, thereby failing to recognize an additional component of a mixed germ cell tumor.

Attempts to remove most of the tumor by radical surgical resection have NOT been shown to improve the cure rate of patients with pure germinomas of the brain, and are associated with higher complication rates, some of which may be very serious and irreversible. However, in recent studies from both North America and from Europe, patients with mixed malignant germ cell tumors do appear to have improved cure rates following gross total resections of the primary tumor. Furthermore, in the case of tumors consisting of mature or immature teratoma components, these components are not so responsive to irradiation or chemotherapy, and are indeed best eradicated by surgical resection. The best time to undertake such a surgical resection is not necessarily at initial diagnosis, but through delayed surgical resection, after initial chemotherapy has shrunk down the other elements of the germ cell tumor, and a residual tumor mass remains, indicative most likely of mature or immature teratoma.

Sometimes, the mature or immature teratoma component of the tumor is so substantial, that the tumor actually increases in size with initial chemotherapy. This uncommon but well recognized scenario is known as “The Growing Teratoma Syndrome”, and when this happens, it is critical that the treating physicians recognize it for what it is, a situation requiring prompt surgical resection. It is NOT an indication that chemotherapy has failed and all hope for cure is lost unless immediate high dose radiation therapy or – even worse – far more intensive chemotherapy – is implemented! Resection of the teratoma should be undertaken, and then the original plan of treatment continued.

The Role of Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Germ Cell Tumors of the Brain

Germinomas of the brain are amongst the most radiation-curable of all tumors. The current ”gold standard” in North & South America, Europe and Japan is clearly initial chemotherapy followed after 3-4 cycles (9-16 weeks) by radiation therapy, delivered to encompass the ventricular system of the brain (NOT the entire brain or the spinal cord, unless the patient has evidence of tumor spread to these regions) with an additional boost of irradiation to the site of the tumor. This approach will produce a cure for the tumor in over 90% of cases of germinoma of the brain. However, in pre-pubertal children, as well as children already presenting with some damage as a consequence of their tumor, even the current standard of radiation therapy treatment alone can produce some impairment of learning abilities, memory and intellectual functions. Accordingly, studies in North America, Europe and Japan in recent years have been trying to reduce the doses of radiation therapy down to a safer level, by giving the radiation therapy after a few courses of chemotherapy. There are now several published studies from both North America and from Europe demonstrating clearly that such an approach, combining chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy at a reduced dose to the ventricular system of the brain and a boost localized only to the tumor site, will result in over a 90% cure rate in children with localized brain germinomas. The Japanese Germ Cell Tumor Study Group is currently conducting a clinical trial in which children with germinoma who achieve complete or near complete responses to initial chemotherapy undergo partial brain irradiation without any boosts to the primary tumor site – although results from this study are not yet reported.

Finally, the optimal treatment for those children with the more difficult and aggressive mixed malignant germ cell tumors of the brain, continues also to be somewhat controversial. These tumors are far less sensitive to chemotherapy than germinomas and are not cured by radiation therapy alone. The currently accepted treatment approach is to use several cycles of more intensive chemotherapy, followed by radiation therapy. Results from such an approach indicate cure rates of around 60% to 80%. The controversy surrounds how wide a field of radiation therapy needs to be applied and at what dosages. European investigators have reported that high dose radiation therapy directed only to the tumor site, need be employed. However, the North American “standard” approach continues to include irradiation to the entire brain and spinal cord at full doses (3600cGy) to these children -many of whom are pre-pubertal or else have underlying cognitive/developmental dysfunction at diagnosis due to their tumors – and therefore at much greater risk for long term toxicities of the radiation therapy.

Our understanding of the molecular biology of these malignant germ cell tumors has grown substantially in recent years, thanks largely to the work of Japanese investigators who, because of the generalized neurosurgical practice of obtaining radical surgical resections at diagnosis for children with these tumors, and the increased prevalence of these tumor in the far East, have been able to study tumor tissue on large numbers of such patients. As a result, we can now identify molecular abnormalities in the individual malignant germ cell tumors which can indeed be targeted by novel biological drugs specific for these molecular targets. This author is specifically piloting a clinical trial for select children with ultra-high-risk newly diagnosed mixed malignant germ cell tumors of the brain with a regimen that incorporates such biologically-targeted therapy in addition to intensive chemotherapy -and avoidance of radiotherapy for the youngest of children for those with cognitive/developmental impairments at initial diagnosis.

The Management of Children with Recurrent Germ Cell Tumors of the Brain:

Only a minority of patients with brain germinomas will develop a recurrence. This is likely to happen in patients who have received irradiation to the tumor site only (with or without chemotherapy) or, for whatever reason, have received chemotherapy only. Such patients can be virtually uniformly cured by appropriate radiation therapy. However, for those patients who have already received focal irradiation, the toxicities of the added irradiation are not minor, and must be considered carefully. For children who do develop recurrence of tumor despite prior irradiation and chemotherapy, an approach incorporating very high dose (marrow destructive) chemotherapy and blood cell rescue has been shown to be associated with 80% cure rates.

The treatment of children with recurrence of mixed malignant germ cell tumors depends upon the predominant cell type at recurrence. If germinoma, then treatment should be as indicated above for pure germinomas. If teratoma, then surgical resection will be the crucial form of treatment. If the more malignant GCT elements predominate (eg. yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma, embryonal carcinoma) then one has a much tougher battle ahead. The best approach employs at least two stages; the first, use of chemotherapy to achieve a state of minimal residual tumor; the second stage, the use of marrow ablative chemotherapy with blood cell rescue as indicated above for pure germinomas; and finally, still under investigation by this author, the use of biologically-targeted therapies, as discussed above. The initial two stage approach has resulted in about 50% cure rates for children with recurrent mixed malignant germ cell tumors of the brain. A critical component here is the ability to achieve a state of minimal residual tumor with further chemotherapy. It is hoped that the addition of the biologically-targeted therapies will improve further the outcomes for such children. However, it is imperative that new drugs and drug combinations be identified that will have the best chance of achieving initial good tumor responses for such patients with recurrent tumor. One approach that we and other institutions in North America have undertaken together is a pilot trial using the combination of gemcitabine, paclitaxel and oxaliplatin –drugs that have been shown effective in recurrent germ cell tumors arising outside the brain in adults. The pilot results in a small number of such patients have been highly encouraging for patients whose germ cell tumors have grown despite initial standard chemotherapy regimens..

Conclusion:

The treatment of these rare germ cell tumors of the brain is associated with high cure rates, but their rarity and complexity demand that diagnosis and treatment be undertaken at major pediatric-oriented medical centers, or at the very least, in consultation with physicians from such centers. One must remember that one may be treating several different germ cell tumor components within the same patient’s tumor, each with different biological behaviors and therefore demanding different approaches to treatment at the same time.

It is essential that an accurate diagnosis is made to ensure that a patient is neither under-treated nor over-treated. Finally, new drug programs must be developed in order to improve the cure rate for children whose germ cell tumors of the brain recur, and ultimately to employ more effective drug treatments in the initial management of such children to prevent any recurrences from the outset.

Written for the Childhood Brain Tumor Foundation by Dr. Jonathan Finlay, Photo provided by Dr. Gilbert Vézina. E-mail: jfinlay@chla.usc.edu

Updated January 2020.

Journal Publications- resource list provided by Jonathan Finlay,

Fangusaro J et al. Phase II Trial of Response-Based Radiation Therapy for Patients with Localized CNS Nongerminomatous Germ cell Tumors: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. J Clinical Oncology 2019. 37 (34): 3283-3290.

Abu Arja MH, Conley S, Salceda V, Al-Sufiani F, Boué DR and Finlay JL. Brentuximab-vedotin maintenance following chemotherapy without irradiation for primary intracranial embryonal carcinoma in Down syndrome. Child Nerv Syst 2018. 34(4): 777-780.

Al-Naeeb AB, Murray M et al. Current Management of Intracranial Germ Cell Tumors: An Overview. Clinical Oncology 2018. 30: 2014-2014.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0936655518300360

Calaminus G et al. Outcome of Patients with Intracranial Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors -Lessons from the SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 Trial. Neuro-oncology 2017.19: 1661-1672.

Ichimura K et al. Recurrent Neomorphic Mutations of MTOR in Central Nervous System and testicular Germ Cell Tumors may be Targeted for Therapy. Acta Neuropathologica 2016. 131:889-901.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26956871

Wong K et al. Re-irradiation of Recurrent Pineal Germ Cell Tumors with Radiosurgery: Report of Two cases and Review of Literature. Cureus 2016. 8 (4): e585.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4882159/

Goldman S et al. Phase II Trial Assessing the Ability of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with or without Second-Look surgery to Eliminate Measurable Disease for nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015. 33: 2464-2471.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4507465/

Murray MJ, Bartels U, Nishikawa R et al. Consensus on the Management of Intracranial germ Cell Tumors. Lancet Oncology 2015. 16: e470-e477.

Consensus on the management of intracranial germ-cell tumours

Acharya S et al. Long-Term Outcomes and late Effects for Childhood and Young Adulthood Intracranial germinomas. Neuro-oncology 2015. 17(5): 741-746.

https://academic.oup.com/neuro-oncology/article/17/5/741/1108996

Baek HJ et al. Myeloablative Chemotherapy and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in patients with Relapsed or Progressed Central nervous System Germ Cell Tumors: Results of the Korean Society of Pediatric Neuro-oncology (KSPNO) S-053 Study. Journal of Neuro-oncology 2013. 114: 329-338.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11060-013-1188-1

Calaminus G et al. SIOP CNS GCT 96: Final Report of Outcome of a Prospective, Multinational Nonrandomized Trial for children and Adults with Intracranial Germinoma, Comparing Craniospinal irradiation Alone with Chemotherapy followed by Focal Primary Site irradiation for patients with Localized Disease. Neuro-oncology 2013. 15: 788-796.